The Unseen Lens: How Religious Framing Shapes Pakistan's View of India

-

Chief Editor

Chief Editor - 27 Jun, 2025

In the intricate tapestry of South Asian geopolitics, narratives are often as potent as policy. Few threads are more contentious than the discourse around religious nationalism, particularly the frequent condemnations of “Hindutva” emanating from Pakistani intellectual and media circles. From television studios to university seminars, the critique is sharp, often portraying India as succumbing to a dangerous, religiously driven majoritarianism. Yet, a closer, more introspective look at the very language employed in these Pakistani critiques reveals a profound, and perhaps unsettling, irony.

I would argue that much of the Pakistani intellectual and media discourse, even when delivered by those who identify as liberal or progressive, operates within a linguistic and conceptual framework so deeply permeated by Islamic religious terminology that it creates a significant blind spot. This unacknowledged “religious lens” skews their perception, leading to a curious hypocrisy: they vehemently criticize religious nationalism abroad while arguably failing to recognize the pervasive influence of their own religious framing at home. The result is a dialogue that, despite its intentions, often falls short of true intellectual consistency and hinders genuine cross-border understanding.

The Drumbeat of Devotion: Language in Pakistani Public Discourse

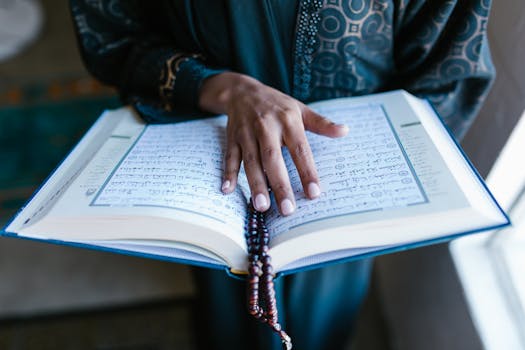

To truly grasp this phenomenon, one must immerse oneself, even briefly, in the texture of Pakistani public discourse. Tune into a prime-time talk show, skim a leading newspaper, or listen to a podcast featuring the nation’s “thought leaders” – even those celebrated for their critical or reformist views. What becomes immediately apparent is the near-ubiquitous presence of Islamic religious terms. Words like “Islam,” “Muslim,” and “Ummah” are not merely used in discussions about theology or faith; they are interwoven into the very fabric of political analysis, economic commentary, social critique, and even debates on national identity and foreign policy.

Consider a discussion on national cohesion. It might naturally drift towards the concept of the “Ummah,” implying a shared identity and destiny rooted in global Islamic solidarity. When dissecting foreign policy, the plight of “Muslims” in various parts of the world often becomes a primary moral compass, regardless of the immediate geopolitical intricacies. Even in conversations ostensibly about secular governance or economic development, an underlying assumption about Islamic values, principles, or historical precedents frequently informs the arguments. This isn’t always overt preaching; it’s often a subtle, ingrained linguistic habit, a default setting that frames the conversation.

The effect is profound. For an outsider, or indeed for many within Pakistan who may not consciously register it, this constant invocation imbues every discussion with a religious subtext. It normalizes a worldview where religious identity, religious history, and religious imperatives are not just one factor among many, but often the foundational elements through which all other phenomena are interpreted. This deep immersion means that for many, these terms become synonymous with universal values or objective truths, making it challenging to differentiate between religiously informed thought and purely secular analysis. The language itself acts as a constant reminder, an almost subliminal suggestion, that the world is to be understood, and problems solved, through a particular faith-based paradigm.

The Silent Chasm: A Perceived Indian Contrast

Now, juxtapose this linguistic environment with the very object of its frequent criticism: India. For years, Pakistani intellectuals have rightly highlighted the rise of majoritarian tendencies in India, often encapsulated under the banner of “Hindutva.” Concerns about minority rights, secular erosion, and the redefinition of national identity along religious lines are legitimate points of academic and journalistic inquiry.

However, from the vantage point of this observation, there exists a striking difference in the pervasiveness of explicit religious terminology in India’s general public discourse and mainstream media. While political rallies in India may indeed reverberate with chants of “Jai Sri Ram” and nationalist fervor, and while certain segments of the media or political parties may overtly champion “Hindu” identity or “Sanatan” values, these terms are, arguably, not as universally or subtly integrated into the day-to-day conversations of Indian mainstream intellectuals, news channels, or general public discussions.

In India, discussions around economic policy, democratic principles, social justice, or even foreign relations, while often heated and diverse, tend to rely more heavily on what might be called a civic or constitutional vocabulary. When religious references appear, especially outside of specific religious programming or politically charged events, they are often perceived as a deviation or an emphasis, rather than a baseline. This is not to deny the existence or impact of Hindu nationalism, but to highlight a difference in the default linguistic landscape of public intellectual engagement.

The irony then becomes stark: how can a discourse, saturated with phrases like “Inshallah,” “Muslim Ummah,” or “Islamic principles,” castigate another society for its perceived religious nationalism, when the very terms of that criticism are themselves deeply embedded in a religious framework? This perceived double standard begs the question: is the critique truly about religious nationalism as a universal phenomenon, or is it implicitly, and perhaps unconsciously, about the nature of the religion in question?

The Unseen Mirror: Societal Self-Unawareness

This brings us to the crux of the matter: societal self-unawareness. A significant segment of Pakistani society, including its intellectual and media elite, appears largely oblivious to, or at least underestimates, the profound extent to which their own societal and intellectual fabric has been shaped by an Islamic or fundamentalist lens. This is not an accusation of malice or conscious deception, but rather an observation about the insidious nature of deeply ingrained cultural and ideological influences.

Since its inception, Pakistan’s state ideology has been inextricably linked with Islam. This has permeated education systems, public institutions, and cultural norms. Over decades, a vocabulary and a conceptual framework centered around Islamic identity have become so normalized that they often cease to be recognized as explicitly religious. They become “just how we talk,” “just how we think,” or “just how things are.”

This normalization creates an “internal religious lens” that skews perception in critical ways. When an intellectual from this background observes an external society, their own, often unexamined, religious framework acts as a filter. Expressions of religious identity in India, for example, are immediately flagged as problematic or majoritarian, while the equally pervasive (and perhaps more foundational) religious expressions within their own society are seen as neutral, normal, or even intrinsically good. It’s akin to someone living in a perpetually green-tinted room criticizing the “greenness” of another room, without realizing their own perception is already colored.

This blind spot has several detrimental impacts. Firstly, it hinders genuine self-critique. If one cannot recognize the religious underpinnings of one’s own discourse and society, it becomes impossible to meaningfully address potential issues of religious exclusivity or fundamentalism at home. Secondly, it simplifies complex socio-political realities. The nuanced interplay of culture, ethnicity, economics, and religion in India (or any non-Muslim society) is reduced to a simplistic narrative of “rising Hindutva,” ignoring the multiplicity of factors at play. Finally, it poisons the well of international dialogue. When criticism comes from a position of unacknowledged internal inconsistency, it is easily dismissed as hypocritical, thereby undermining the validity of potentially legitimate concerns and making genuine understanding across borders even more elusive. The discussion devolves into accusations and counter-accusations, rather than productive engagement.

The Intellectual Conundrum: Examining Specific Voices

It is important to emphasize that this observation extends even to prominent Pakistani intellectuals who are widely respected for their critical thinking and commitment to secular or progressive values. Figures like Dr. Pervez Hoodbhoy, known for his incisive critiques of religious extremism and calls for rationalism in Pakistan, or Syed Muzammil Shah, who engages with political and social issues, and “The Pakistan Experience” podcaster, who fosters open conversations on Pakistani society, are prime examples.

Their work often involves challenging established norms and pushing for greater intellectual honesty. Yet, even in their discourse, one can, to some extent, detect the subtle influence of this pervasive religious framing. It might manifest not as an endorsement of fundamentalism, but perhaps as a default assumption of Islamic morality in discussions of governance, or an almost unconscious reliance on Islamic historical precedence when discussing societal evolution. Their critiques of India, while often sharp and valid regarding the rise of Hindutva, sometimes land with a peculiar weight, perhaps because the critic’s own linguistic canvas is painted with the very hues they are denouncing elsewhere, albeit in a different religious context.

This is not a condemnation of these individuals, but rather an illustration of how deeply ingrained societal influences can be. Even brilliant minds, committed to objective analysis, may find themselves operating within conceptual frameworks that are a product of their environment. The challenge lies in recognizing these frameworks and actively deconstructing them for greater consistency in critique.

Beyond the Rhetoric: A Call for Introspection

The critical examination of “Hindutva” is undoubtedly essential, but it must be matched by an equally rigorous self-reflection from those conducting the critique. The irony of criticizing religious nationalism in India while operating within a public discourse that is itself profoundly shaped by Islamic religious terminology is a significant intellectual and societal hurdle.

For Pakistan, embracing true secularism and fostering a pluralistic public sphere requires more than just condemning religious majoritarianism in others. It demands a painful, yet necessary, introspection into the very language and underlying assumptions that define its own intellectual and media landscape. This means recognizing that the constant invocation of “Islam,” “Muslim,” and “Ummah” in all spheres of discourse, however well-intentioned, can inadvertently normalize a religiously tinted worldview that struggles to perceive itself clearly while critiquing others.

Such introspection would not diminish the validity of concerns about religious nationalism wherever it manifests. Instead, it would lend greater moral and intellectual weight to those critiques, fostering a more consistent and universally applicable standard for secularism, pluralism, and human rights. Only when the mirror is held up to oneself with the same rigor it is applied to others can truly productive and honest conversations begin across the deeply divided subcontinent. The path to genuine understanding and progress demands a self-awareness that transcends rhetoric and embraces the unseen lens.